Change in average surface temperature

OSLO/LONDON — World governments are likely to recoil from plans for an ambitious 2015 climate change deal at talks next week as concerns over economic growth at least partially eclipse scientists' warnings of rising temperatures and water levels.

“We are in the eye of a storm,” said Yvo de Boer, the United Nations climate chief in 2009, when a summit in Copenhagen ended without agreement. After Copenhagen, nations targeted a 2015 deal, to enter into force from 2020, with the goal of averting more floods, heat waves, droughts and rising sea levels.

The outline of a more modest 2015 deal, to be discussed at annual U.N. climate talks in Warsaw Nov. 11-22, is emerging. This deal will not halt a creeping rise in temperatures but might be a guide for tougher measures in later years.

Since 2009, scientists' warnings have become more strident and new factors have emerged, sometimes dampening the impact of their message that human activity is driving warming.

The U.S. shale boom helped push U.S. carbon emissions to an 18-year low last year, for instance, but it also shifted cheap coal into Europe, where it has been increasingly used in power generation.

Despite repeated promises to tackle the problem, developed nations have been preoccupied with spurring sluggish growth. Meanwhile, recession has itself brought about a drop in emissions from factories, power plants and cars, a phenomenon that may prove short-lived.

Emerging economies such as China and India, heavily reliant on cheap, high-polluting coal to end poverty, are reluctant to take the lead despite rising emissions and pollution that are choking cities.

“Our concern is urgency” in tackling climate change, said Marlene Moses of Nauru, chair of the Alliance of Small Island States whose members fear they will be swamped by rising sea levels. “Vague promises will no longer suffice.”

She wants progress when senior officials and environment ministers from almost 200 nations meet in Warsaw to discuss the 2015 deal, in addition to climate aid to poor nations and ways to compensate them for loss and damage from global warming.

Yet many governments, especially in Europe, are concerned that climate policies, such as generous support schemes for solar energy, push up consumer energy bills.

Some want to emulate the success of the United States in bringing down energy prices via shale gas - a fossil fuel that can help cut greenhouse emissions if it replaces coal, but at the same time can divert investments from even cleaner forms of energy.

Patchwork of pledges

Many Warsaw delegates say the 2015 accord looks likely to be a patchwork of national pledges for curbing greenhouse gas emissions, anchored in domestic legislation, after Copenhagen failed to agree a sweeping treaty built on international law.

The less ambitious model is a shift from the existing Kyoto Protocol, which was agreed to in 1997. That set a central target for emissions cuts by industrialized countries, and then shared them out among about 40 nations.

However, Kyoto has not worked well, partly because the United States did not join. The U.S. objected that the treaty would cost U.S. jobs and set no targets for big emerging nations. Russia, Canada and Japan have since dropped out.

Warsaw will be the first meeting since the U.N.'s panel of climate scientists, the main guide for government action, in September raised the probability that climate change is mainly man-made to 95 percent from 90 and said that “substantial and sustained” cuts in emissions were needed.

Treaty

A leaked draft of a second report by the panel, due in March 2014, suggests climate change will cause heat waves, droughts, disrupt crop growth, aggravate poverty and expose hundreds of millions of people to coastal floods as seas rise.

“Evidence is accumulating weekly, monthly as to how dangerous this will be,” said Andrew Steer, head of the World Resources Institute think-tank in Washington. Steer claims every year of delay adds $500 million to the eventual cost of fixing climate change.

He said that there were signs of progress, such as a plan in June by U.S. President Barack Obama to achieve a goal for cutting emissions by 2020 and the start of carbon trading in China. However, “they don't add up” to a solution, Steer added.

Any deal weaker than a treaty for shifting from fossil fuels to renewable energies is anathema to poor nations.

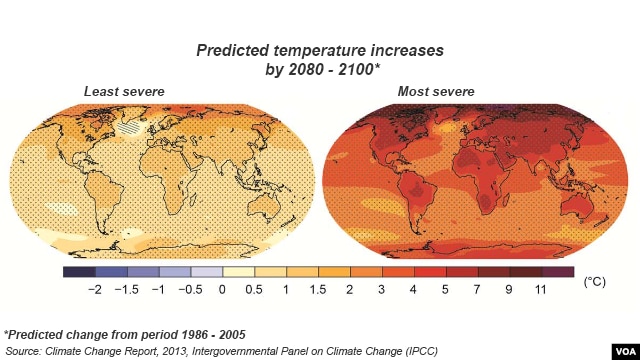

The 2015 deal is unlikely to include deep enough emissions cuts to achieve a U.N. goal set in 2010 of limiting temperature rise to below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit).

Temperatures have already risen by 0.8 C (1.4 F) since the Industrial Revolution, causing more heat waves, floods and rising sea levels despite a hiatus in the pace of warming at the Earth's surface so far this century.

A more flexible approach for 2015, as championed by the United States, raises risks that many nations will simply set themselves weak goals and hope others take up the slack.

However, that route may have a better chance of ratification by national parliaments. The hope is that negotiators will find a way to compare the ambition of promises and develop a mechanism to ratchet the weak ones up in coming years. |

|